Utah Guard soldiers bring their language skills to a new battlefront — as contact tracers in war against coronavirus

By Nate Carlisle The Salt Lake Tribune April 27, 2020

Lt. Col. Scott Chalmers once deployed to Afghanistan to communicate with locals there for the U.S. Army. Now he’s overseeing soldiers trying to tell Utahns about the coronavirus.

“Our job is to help the community wherever we’re at,” said Chalmers, the administrative officer for the Utah National Guard’s 300th Military Intelligence Brigade.

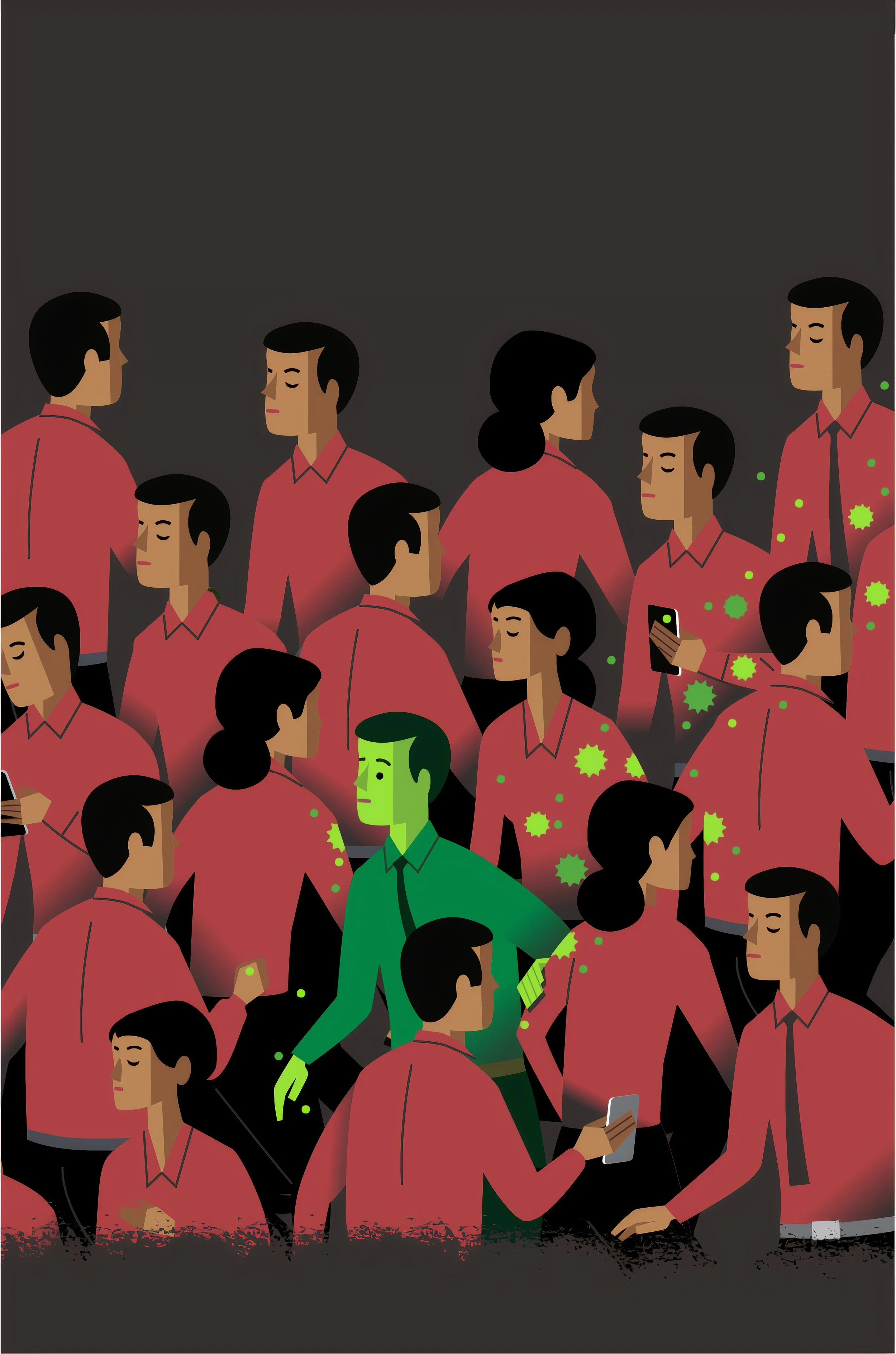

Twenty soldiers from the brigade are among the battalion of state employees who have volunteered to do what’s called contact tracing. That’s when phone calls or other communications are made to people who might have been infected by a COVID-19 patient.

Contact tracing is considered vital in the effort to contain the virus. About 300 state employees have volunteered to be trained to make the calls. It’s assumed a number of the people who will be notified will not be native-English speakers.

That’s where the 300th steps in. Foreign languages are the brigade’s speciality. The linguistic unit provides a variety of translation services. Chalmers said many of the 300th’s soldiers learned foreign languages while serving missions for Utah’s predominant faith, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, which sends proselytizers to nations around the globe.

“This [coronavirus] mission is exactly what I would hope to do,” said Capt. Aaron Bybee, commander of the 142nd Military Intelligence Battalion’s Alpha Company. The battalion is a component of the 300th.

Bybee is fluent in Portuguese and speaks a little Spanish. So far the people he has called — whatever language they speak — have usually been scared at the news they came into contact with someone exhibiting coronavirus symptoms. Even so, they appreciate the state letting them know.

“So it just helps us to be able to calm them,” Bybee said, “and be that calm, confident voice they can rely on as we’re making the calls.”

Bybee is a part-time soldier. In his civilian life, the 37-year-old Sandy resident owns three businesses. One cleans semis, another makes promotional videos, and he co-owns a pest-control company.

He and other contact tracers are doing those jobs from home. Calls are made over a Utah Department of Health online system.

“We are neighbors helping neighbors,” Bybee said, “trying to help people get through this crazy pandemic.”

Chalmers, who works full time for the Utah National Guard, speaks Spanish. He says the training he and the soldiers in the 300th have received includes how to bridge cultural divides.

When he deployed to Afghanistan, he went out with a translator who spoke the local language. Chalmers listened to the locals’ concerns and communicated those to the combat soldiers with the aim of keeping the peace.

“If bullets are flying," Chalmers said, “I’ve failed to do my job.”

As for now, he doesn’t see much overlap between what he and other soldiers in the 300th have been trained to perform in combat and what they are doing with contact tracing. All the contact tracers are following a script and directives from the Utah Department of Health.

Still, Chalmers said, the Guard can always be counted on to help in a crisis. “We have to be prepared at a moment’s notice."

Besides contact tracing, the 300th has helped the Utah Department of Health translate various coronavirus documents into foreign languages, including Spanish, Arabic, Nepali, Russian, Karen, French, Chinese, Vietnamese, Portuguese, Burmese, Farsi and Korean.