In Pickens County, every day is play day

In Pickens County, every day is play day

By Sara Gregory, The Post and Courier, September 12, 2022

Photos usable. (word count: 2265)

The first rule of Play Club is you can’t hurt anyone.

That’s actually the only rule.

On a Thursday afternoon after the last school bell rings, several dozen third, fourth and fifth graders from Pickens County’s Central Academy of the Arts stream out of the school and scatter round the yard. How to spend the next two hours is entirely up to them.

Quickly there are shrieks from a basketball court where several have started a game of chase. At a picnic table, two girls pull out a notebook to continue writing their novel. Children sit in a row in the shade of the school building talking and eating snacks. Three boys stand in boxes — they are actually train cars, one declares — going chugga chugga down the sidewalk.

Kevin Stinehart just watches. Stinehart, one of two adults supervising, likens himself to a lifeguard. If someone is in danger, he will intervene. Otherwise, the students are in charge.

“It’s good for our souls just to watch them play and be kids,” Stinehart said.

The amount of time children have for unstructured free play has been declining for decades, replaced by activities managed by well-intentioned adults. Today’s children spend about half as much time playing outside each week as their parents did, one study found. COVID-19 caused more disruptions. Play dates and recess were curtailed for safety concerns. Even as those worries have subsided, efforts to remediate learning losses before, during or after school are replacing play in many places.

When Stinehart started Central Academy’s Play Club years ago, the fourth grade teacher just thought children needed more time to play like he did as a child, free from the adult gaze. Only after the club started did he begin to fully realize how seriously play matters for developing children.

There was one child at his school who teachers had never seen smile before the boy joined Play Club. He started making friends and almost instantly his behavioral issues — one week three different teachers had sent him to the principal’s office — disappeared. Teachers saw similar behavior improvements schoolwide.

Then there were the academic benefits: A researcher who studied Central Academy’s club found that participating students did better on reading and math tests.

Play would be important even without those benefits, Stinehart and others stress. Today’s children have high rates of anxiety and depression and overall feelings of isolation, and helping them socially and emotionally was the school’s ultimate goal.

But for parents and educators alike who have worried over the learning disruptions caused by the pandemic, the academic benefits are noteworthy perks.

“We didn’t start Play Club to raise test scores,” he said. “All of that was just icing on the cake.”

Teaching play

Central Academy is in the cradle of play.

The Pickens County superintendent is a longtime play advocate. Danny Merck traveled to Finland in 2018 and after seeing how Scandinavian schools take 15-minute breaks every 45 minutes, Merck came home and encouraged his principals to add a second recess. Once you see that kind of joy, you try to emulate it as best you can, he said.

Pickens is also home to Clemson University, where a national coalition that promotes the importance of lifelong play is headquartered. It was at the group’s annual conference one year where Stinehart met Lenore Skenazy and got the idea for Play Club.

Skenazy made headlines over a decade ago after she let her 9-year-old ride the New York City subway unchaperoned. She wrote a blog, and later a book, called Free-Range Kids and is one the most outspoken advocates for free play and children’s independence. Her nonprofit, Let Grow, created the Play Club concept and helps schools around the country create their own.

“We’d like to make sure that childhood isn’t so cultivated and so bubble-wrapped,” she said.

Skenazy knew many parents are nervous about the idea of free play. Many of those with grade-school-aged children are young enough to have grown up without experiencing it much themselves. Her group decided to anchor the Play Clubs at schools because children are there already and it’s generally a place that parents trust. Play Clubs have rules that truly unstructured free play doesn’t, but Skenazy’s group saw the clubs as a way to introduce the idea.

Stinehart loved the club concept and it was an easy sell to his principal, Tish Goode. The two had talked frequently about how their students just didn’t seem to know how to play. Many had underdeveloped social skills, well before the pandemic exacerbated those concerns.

Goode, who went to the conference with Stinehart, said she started to realize children at her school were struggling to play simply because they were not given many opportunities to learn how. When adults solve every single conflict, children don’t learn how to do so themselves.

Central Academy’s club operates like most. Stinehart opens enrollment twice a year, filling a fall and spring cohort. There’s always a waiting list — 81 students signed up for 40 spots in the current cohort — so this year he added a third section. Other teachers help supervise on a rotating basis. The club meets weekly on Thursdays after school ends.

Parents and students alike sign a contract agreeing to the rules. No, you can’t hurt anyone. But they also agree children will work out problems themselves. It’s not the adults’ job to mediate interpersonal conflicts. It’s not their job to entertain or ensure children are having fun, either.

This makes Play Club different from recess. At recess, Stinehart will intervene if he sees a child say, cutting the line to go on the slide out of turn. During Play Club, he’ll say nothing.

But what happens is students start to police themselves. A few years ago, Stinehart watched as a group of students decided to make a big pile of leaves. Another child strolled over and sat in the middle of the pile, clearly trying to instigate something. At first, the others complained and begged the boy to move. He doubled down. The adults were wary, nervous they might need to intervene. Then the group decided the leaf pile was big enough for them all. When his behavior stopped getting a rise out of the others, the boy got bored and went to play somewhere else.

Students won’t always solve problems so easily, Skenazy said, but they get better with practice.

“You’re constantly figuring out how to make things happen in the best way,” she said. “That means trying out new ways that might not work, but it doesn’t matter because it’s just play.”

Goode, the principal, was regularly dealing with 200 or more disciplinary incidents a year. Nearly all were from playground fights. Last year, less than 50 crossed her desk. She credits that to Play Club’s influence. She sees students at recess talking out problems instead of fighting.

A head taller

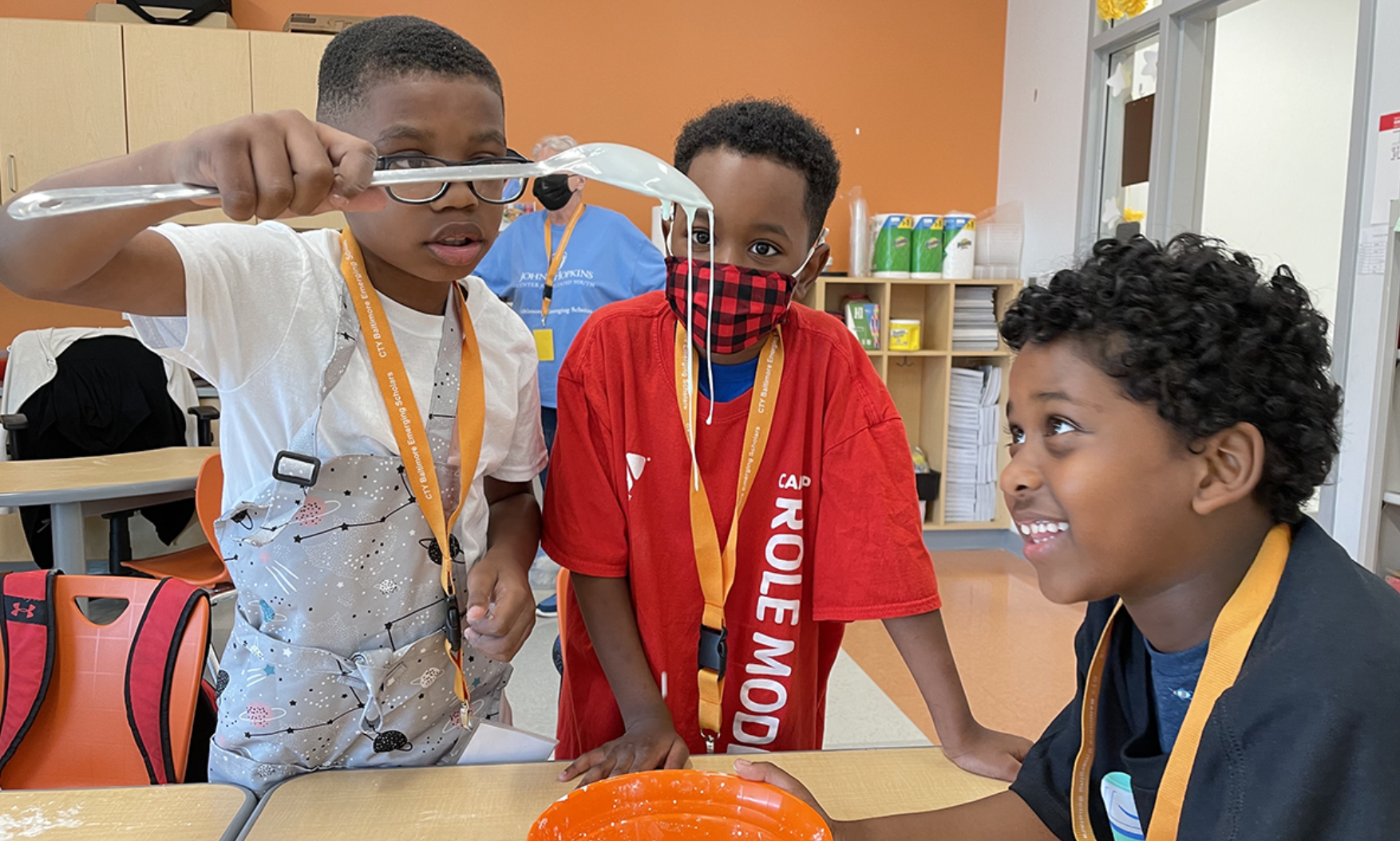

A lot of lessons are imparted during what can look like a carefree activity.

Free play builds a child’s sense of independence. Children learn critical thinking skills and how to interact with others in the world. They grow confidence in their own ability to solve problems.

Peter Gray has been studying play since the 1980s, a decade that marked the biggest decline in the amount of time children spend each week playing. Gray helped develop the Play Club model based on his research showing the value not just of play, but of mixed-age interactions.

Play was at its height in the 1950s. Baby Boomers were young and children of all ages would play until the streetlights came on. The time children spent playing each week started to fall in the mid-1960s but two cultural changes in the 80s prompted a more drastic decline.

First, academic expectations rose. The average time students spent at school and on homework increased by 12 hours a week, a product of a nation worried about falling behind academically. Second, several high-profile kidnappings led to a rise in stranger danger. It became bad parenting to not know where your child was at all times. Working parents started to enroll their children in after-school activities that promised to keep them both entertained and safe but which substituted child-led play for play that’s supervised and managed by adults.

Gray’s son was a child in the 1980s and went to an unorthodox school that bucked the trends happening nationwide. His son’s school incorporated significant time for free play and independent exploration, and the experience made Gray want to understand how exactly children learn from play.

The real magic happens when children of different ages play together, Gray has come to believe. There’s a perception that older children will bully younger ones, or dumb down their play. His research and others’ has found the opposite happens.

Older children are empathetic and kinder to younger children than they are to their peers. They like explaining how games work, a skill that flexes their own language abilities. And younger children love playing with the big kids. The saying among people who study this is that children become a head taller when they play. A group of 5- and 6-year-olds who can’t read couldn’t play a game that requires that. With older children’s help, they can usually figure it out.

Translate to the classroom

The study at Central Academy is the first to look into play’s academic benefits.

Educators at the school were eager to collaborate with Melyssa Mandelbaum, a doctoral candidate at Long Island University. Mandelbaum loved the concepts of independence and resilience that Play Clubs try to foster.

Mandelbaum studied the fall 2019 cohort, comparing students who participated with those who were waitlisted. She looked at attendance, tardiness and reading and math test scores.

There ended up not being a difference in the two groups when it came to attendance or tardiness, something that could be because Play Club only meets once a week. But when it came to academics, she found the Play Club students did significantly better in both subjects.

Mandelbaum’s study doesn’t explain why Play Club students did better academically. Her sample was small and she says more research needs to be done. But it speaks to the skills that researchers have observed in free play for years, she said. A student explaining how a game works is using expressing language skills. One keeping track of scores is using math.

“If you’re building those skills, that might actually really translate to the classroom,” Mandelbaum said.

It’s promising to see how even small amounts of free play can boost student achievement, she said. Central Academy’s Play Club just meets weekly for a couple of hours. Mandelbaum said she’s curious if more frequent play would have an even larger effect.

Gray and Skenazy said they weren’t surprised by what Mandelbaum found.

When children are playing, they’re forced to keep trying to find solutions to problems. That’s the same type of critical thinking required in the classroom.

Skenazy hopes educators take note and get some relief from the findings, particularly as she sees schools compensate for COVID learning loss by scaling down recess.

“So many schools have been under the gun in terms of standardized testing that they cut back on free time and free play to give kids more time to quote unquote ‘prepare for the tests,’” she said. “What great news that preparing for the test turns out to be play.”

The Pickens educators were a little bit more surprised by the results. When Stinehart started Play Club, test scores were the last thing on his mind.

Stinehart identifies with Scandinavian educators the superintendent learned about on his visit in 2018. They were surprised the country’s test scores were some of the highest in the world since scores were never their primary focus. It speaks to how critical a child’s emotional and social well-being is to their academic success. You can’t have one without the other.

Just visiting

Out on the playground Stinehart could hardly contain his excitement.

Rainstorms had threatened to push the second play club of the school year inside, but instead the clouds broke and the sun was bearing down. Everyone was hot and sweaty.

“Look at this,” he said, pointing.

Perched on the playground equipment were two girls carefully taking a small parachute and arranging it over top. After putting up their makeshift umbrella, the girls just sat in the shade talking.

Stinehart had never seen students play with the parachute that way or realize it could be used like that. But this is the type of creativity and problem-solving he sees happening in Play Club regularly. Instead of complaining about the heat, the girls just worked together to mitigate it.

The girls’ canopy quickly drew others’ attention and their chat ended abruptly. The playground set had instantly, imaginatively, transformed into a castle under siege.

“I’m infiltrating,” fourth grader Jackson Buier screamed.

“Get out!,” third grader Evelyn Diaz-Cabera told him.

Buier changed his tactic.

“OK, I’m only visiting now. I’m just visiting, not infiltrating,” he said, grinning.

Buier and a few others climbed the slide. The siege ended quickly, everyone’s attention turning elsewhere. Some tossed a beanbag around. A few played on a seesaw. A boy sat by himself on a bench with a box over his head, watching the whole scene through the peephole he’d carved out using Stinehart’s keys. Another child scaled the playground equipment, climbing to the tippy-top of the monkey bars. A single look at the distance to the ground revealed her regret, and she started to climb back down.

“This is too dangerous, I’m not doing this,” third grader Riley Cain said.