Gifted Summer Programs Skew White & Wealthy. Not Baltimore’s — And It’s Free

Gifted Summer Programs Skew White & Wealthy. Not Baltimore’s — And It’s Free

By Asher Lehrer-Small, The 74 Million, August 17, 2022

photos usable. word count: 1565

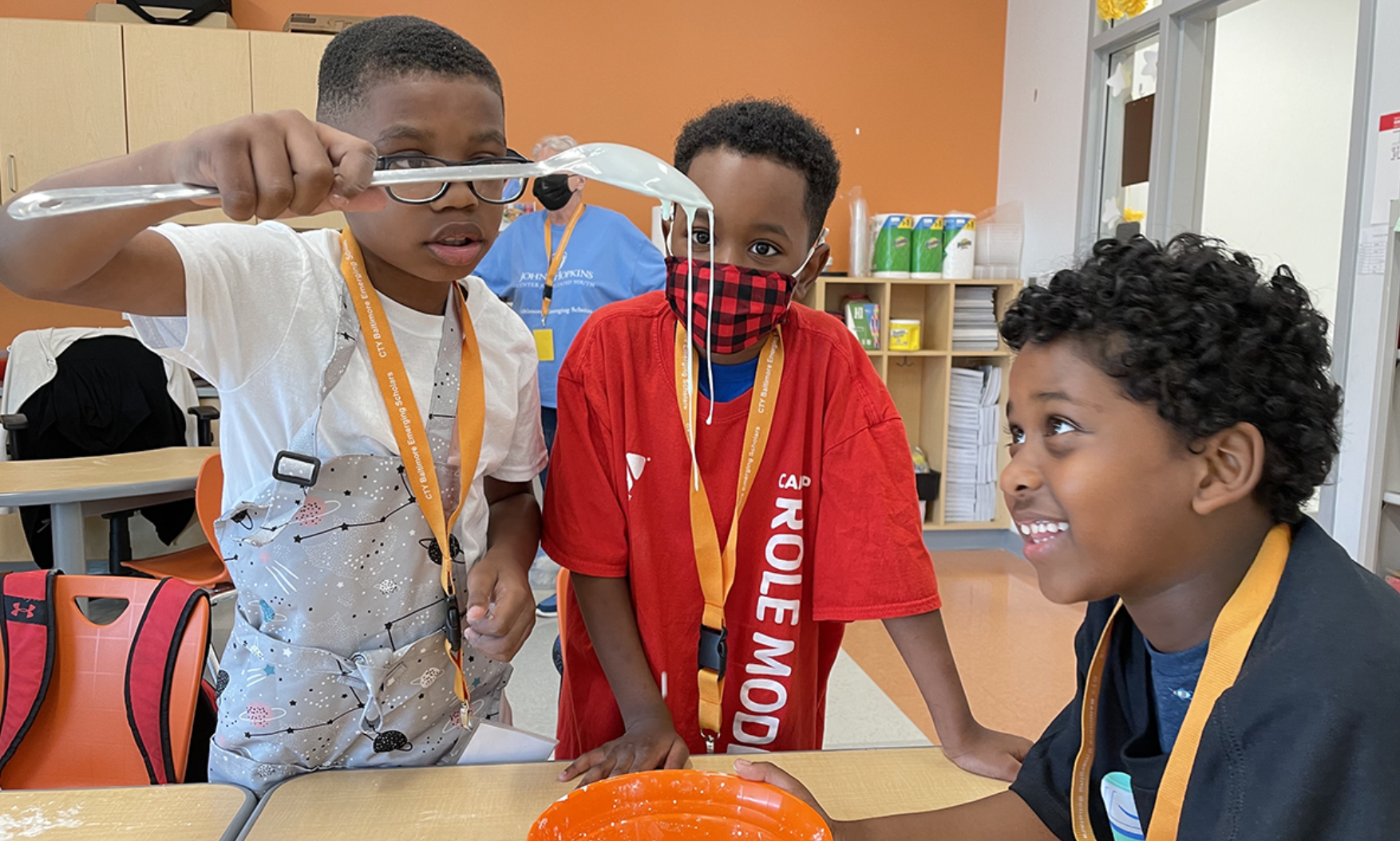

The course is “Cloudy With a Chance of Science,” and James Ramirez places his hand-fashioned tin foil boat into a bin of water, squealing with excitement as he discovers it floats. The first grader and his classmates are learning about density by testing how many pebbles each students’ contraption will hold before it sinks.

Ramirez tosses in every stone from his first handful — quickly surpassing the class record of five pebbles — and rushes back for more as his boat remains above water. The child, who is reserved and hasn’t spoken yet this period, keeps adding weight, laughing and wriggling his shoulders with each successful placement.

“…27, 28, 29…”

He has the attention of the class now and his peers count with him.

“…42, 43, 44…”

With each pebble, Ramirez is doing more than proving he crafted a sturdy ship. He is accomplishing something educators across the country are anxiously hoping he and millions of students like him can do: accelerate their learning to get back on track after COVID.

The first grader is one of 481 youngsters enrolled in Baltimore’s Emerging Scholars program this summer and one of over 15,000 students participating in no-cost summer learning opportunities through Baltimore City Schools. Thanks to COVID relief funds, the 77,800-student district is serving more than twice as many young people as its pre-pandemic max of 9,000, said Ronda Welsh, the district’s extended learning coordinator.

Among the offerings are typical summer school options like credit recovery and career exploration, but also more specialized programs like debate, farm and forest camp, robotics and “Freedom Schools” focused on Black history. The Emerging Scholars program stands out as a camp providing accelerated academic instruction, but with none of the cost or admission requirements typical of gifted programming.

“Our goal was to provide as many opportunities as we could for students in Baltimore,” Welsh told The 74. “We wanted students to not only make progress academically, focusing on math and [English], but also the social-emotional aspect as well as enrichment.”

Young people in Baltimore and nationwide continue to score far below pre-pandemic levels in reading and math tests, with more severe deficits for high-poverty schools. Experts estimate it may take a half-decade to fully recover. Meanwhile, many officials pin their hopes on summer learning efforts like those in Baltimore to make up lost ground.

“Especially because of COVID, the kids are a little behind,” said Claudia Wiseman, a second-grade summer science instructor with Baltimore Emerging Scholars. During the school year, she’s an elementary special educator and said months of Zoom school have meant many young learners still lack basic skills like how to hold a pencil. The students she’s teaching now will be “a little better prepared for second grade,” she hopes.

It’s afternoon pickup time at the Emerging Scholars’ John Ruhrah Elementary School campus, and Ramirez’s mother Christy Miranda arrives. Staff tell her about her son’s latest feat: 63 pebbles.

Miranda beams. The program is helping the family recognize their son’s potential, unlocking academic capacities she didn’t realize he possessed.

“He’s learning a lot,” she told The 74. “I didn’t know he had the ability to do so.”

During the year, her son has few opportunities for rigorous coursework, she said, explaining that his school is “very defunded.”

But this summer is different. Baltimore Emerging Scholars is a six-week gifted and talented program. In collaboration with Johns Hopkins University’s Center for Talented Youth, a global leader in gifted education, the camp provides high-level content in science, math and literacy to rising 1st through 6th graders.

“During the regular year, [school] is just teachers rambling on about stuff I already know about … but this is new material,” said rising fifth grader Basil Coleman. “I’m just having a great time here.”

Unlike most other gifted programs, the camp doesn’t rely solely on test scores for eligibility but rather welcomes virtually any student who is up for the challenge. As a result, the cohort of students is more diverse than the group of students identified for gifted lessons during the academic year. Some 68% of summer students are Black, 14% are Hispanic, 9% are white and 3% are Asian — figures that closely resemble district-wide demographic averages.

Rae Lymer, who manages the program and reviews every student application, explained that anytime a student has a recorded assessment at or above grade level, it automatically qualifies the youngster for the program. If such a metric does not exist, the administrator calls families directly, looking for an alternative qualification such as if the applicant likes to ask lots of questions or thinks outside the box.

“Ninety-nine percent of the time, what I hear is, ‘My kid is completely under-challenged and they’re not motivated by school and so that’s why you’re not seeing scores,’” Lymer told The 74, explaining that the program almost never turns away motivated students.

Youth who choose to participate usually rise to the occasion, the data suggest. While the summer program does not yet have numbers on its academic impact, Emerging Scholars also runs afterschool offerings during the fall and spring. In 2020-21, the most recent data available, the share of participants testing at or above grade level increased 18 percentage points in reading and 39 percentage points in math over the course of the year.

“We’re learning advanced stuff and we’re able to get ahead,” said 11-year-old Ama Amoateng, between stints on the playground during recess. “It makes me feel smarter.”

After engaging in the summer program, “many of these kids will become identified [as gifted],” anticipates Stacey Johnson, spokesperson for Johns Hopkins Center for Talented Youth. “It’s reaching kids we wouldn’t otherwise reach.”

Indeed, parent Torrey Parker said his daughter Skylar got “bumped up” in reading and science last school year, which he believes was “absolutely” because of the work she did in the program.

The rapid growth attests to what education scholars have long posited: That academic talent is equally distributed across all students without regard to race, class or gender — but that access to advanced learning opportunities are not.

“We firmly believe that if opportunities are provided, students will flourish,” said Lymer.

In one reading course focused on mystery novels, rising fifth graders are already 12 chapters into their third book in as many weeks and engaging in what their instructor called “detective work” to predict the ending. In another classroom, second graders concoct oobleck, a water and cornstarch mixture that has both solid and liquid properties, to learn about states of matter and “non-Newtonian fluids.” Down the hall in “Toyology,” first graders study inertia and momentum by unleashing metal and plastic slinkies down a set of stairs.

A classroom of fifth graders peer down the lenses of microscopes at magazine cutouts of the letter “e,” diagramming what they see at various magnification levels. It’s several students’ first time using a microscope and they’re surprised to find what one describes as “static on a TV.”

“They were playing, but they were also learning,” said Toyology instructor Tamika Robinson.

Even the students admit it’s a good time.

“Because it’s called summer school, most of us thought it would be like school … but instead it’s a lot of activities and really engaging,” said Brooke Bennett, 12.

Propelled, perhaps, by rave reviews, the camp has grown nearly three-fold since its 2019 launch and added about 35% new seats this year while transitioning back to in-person programming for the first time since COVID. Staffing challenges, which have curtailed the growth of numerous summer programs across the country, haven’t posed a barrier for Emerging Scholars. In fact, two teachers rather than one work in each classroom under its co-teaching model.

“Many of our teachers come back from year to year because they really respect and value their time with our program,” said Lymer.

As the day winds down, a dozen rising first graders arrive at their last class, Social-Emotional Learning. Shoulders slouch and one student’s head is on his desk. They’ve just watched a YouTube video on how to keep a growth mindset and their instructor Brother Modlin wakes them up with some call-and-response.

“It’s not ‘I can’t do it,’ is it class?” He asks the question by trailing off. “It’s ‘I can’t do it…’”

“YET,” they exclaim, picking up their heads and once again regaining attention.

Modlin works as a school counselor during the year, but was previously a therapist at a juvenile detention center in the city.

“My whole thing as a counselor is about growth mindset,” he told The 74. “We’re going to have bad situations, especially in Baltimore. … If I give them a growth mindset, they can rise out of any situation without depending on anyone but themselves.”

The lessons are having an impact for 10-year-old Akorede Adekola.

“I feel really confident and relief [after SEL class],” he said. “I get to show my feelings and get it all out.”

The program’s approach, coupling rigorous academic work with emotional supports, could be a promising model, believes fourth-grade instructor Michelle Brown-Christian. She scoffs at the idea that the curricula, fashioned for gifted children, should be reserved for only a select few.

“This could work for any child that wants to learn,” she said.