Want to reopen schools? Summer camps show how complicated it’ll be.

Want to reopen schools? Summer camps show how complicated it’ll be.

By Michael Greshko, National Geographic, August 27, 2020

GEORGIA ZENGERLE was on her way. The nine-year-old’s dad wound their car through the hazy green mountains of western North Carolina in mid-July, driving four hours toward the town of Brevard—and the hope for some semblance of normalcy.

Their destination was the all-girls Keystone Camp, a 104-year-old sleep-away establishment that stayed open during the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic—and decided to brave COVID-19 this summer. In a normal year, campers ride horses around the 120-acre grounds, canoe along the Green or Tuckasegee rivers, or zipline through the pine trees of the Blue Ridge Mountains. But this summer, camp came with pandemic precautions.

Georgia wore a mask most times when she was outside of her cabin, and she participated in all her activities with a small, tight-knit “household,” or social bubble. Campfires involved several traffic cones strategically spaced across the main lawn to mark socially distanced seating. When Georgia returned home on July 24, she brought back happy memories—and no COVID-19.

“She understood the reasoning [for the changes], and she understood that this was sort of a special experience: not any less fun, but different,” says Claire Farel, Georgia’s mother and an infectious-diseases physician at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Even through the worst of COVID-19, a portion of summer camps are trying to navigate the pandemic safely. Tom Rosenberg, the president and CEO of the American Camp Association, says that among the more than 15,000 camps in the U.S., 80 percent of overnight camps and 40 percent of day camps have shuttered this summer, and the industry faces a revenue loss of $16 billion.

The stress on us is the most profound I’ve ever experienced running camp.

- PAGE LEMEL, OWNER AND DIRECTOR, KEYSTONE CAMP

To limit risks to children and staff, the camps that opened have reimagined how they operate, according to those interviewed by National Geographic. Many have created protocols to isolate cases before they spark outbreaks. Some have even managed to keep out COVID-19 for weeks at a time.

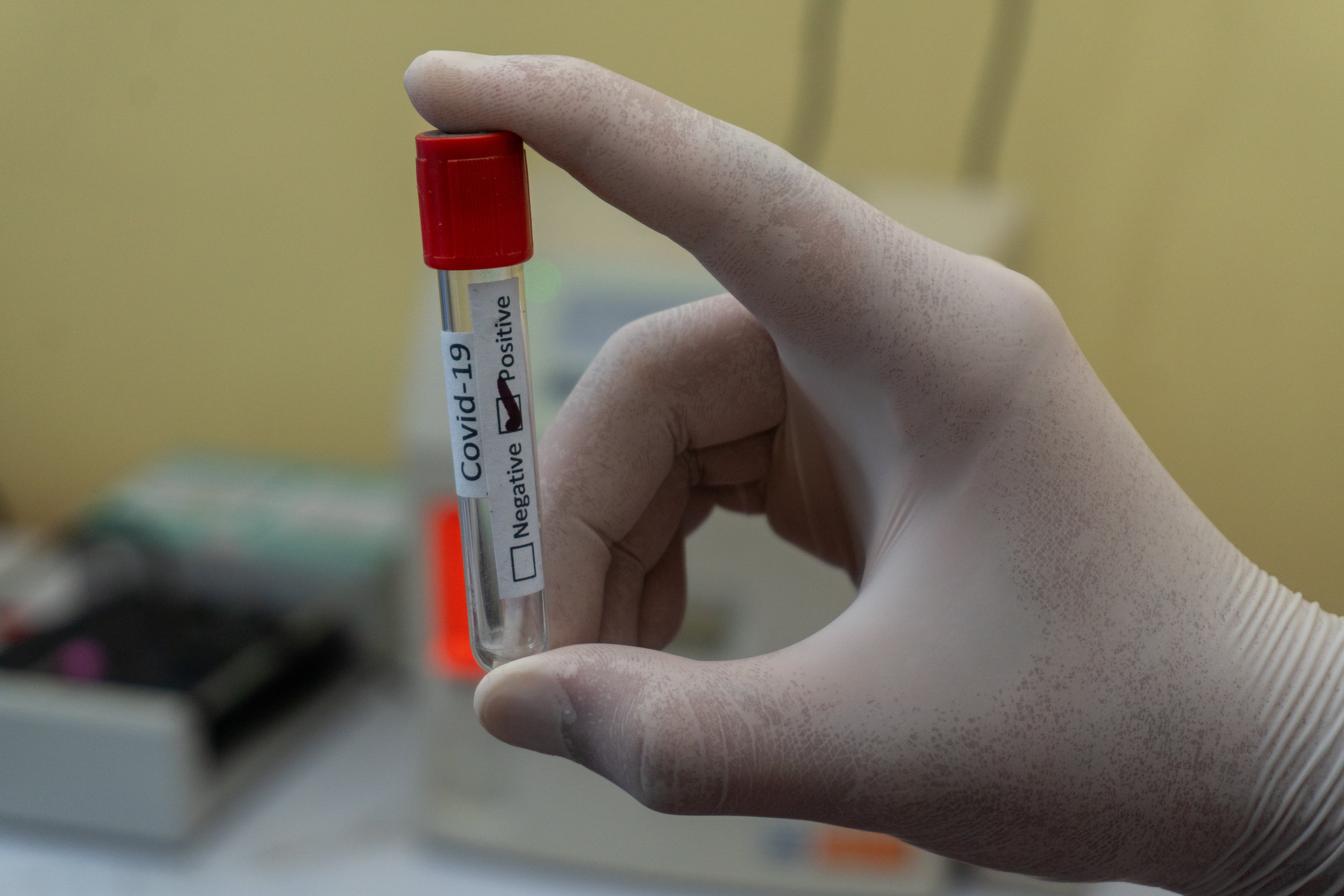

Other camps have not been as lucky, according to a report published by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on July 31. It says that 44 percent of people at an unnamed overnight camp in the state of Georgia—260 of the 597 campers and staff—have tested positive for COVID-19. This outbreak recorded its highest attack rate in some of its youngest campers, with 51 of 100 children from ages six to 10 testing positive. The finding echoes other recent indications that even young children are at risk of COVID-19, contrary to earlier assumptions.

Across the U.S., summer camps could provide a partial preview of what it will take for schools to safely reopen—and the challenges they will face when they do.

‘We’re in Ground Zero’

From head lice to strep throat, camps have always had to contend with infectious diseases. But no summer in recent memory has posed a bigger challenge than this one, according to Page Lemel, the owner and director of Keystone Camp.

Lemel has operated Keystone Camp for 37 years, and it’s been in her family for over a century. Her great-great aunt co-founded the camp in 1916 and ran it through the 1918 flu pandemic. When news of COVID-19 picked up in the spring, Lemel talked with her 89-year-old aunt about Keystone’s polio quarantines in the 1940s.

To operate during the pandemic, Lemel and her staff had to rethink everything, from how children get dropped off (parents stay in the car) to how campers gather for assembly (in masks, on the tennis court, in marked-out circles spaced far apart). Lemel has logged her temperature, and those of her staff, every day since May.

So far, the changes seem to have paid off. With two weeks left in the camp’s two-month season, no staffers or attendees have tested positive for COVID-19, and campers such as Georgia have had the freedom to play outside with friends in a way that’s been next to impossible at home since school closures and local lockdowns began earlier this year. But the daily vigilance takes its toll, especially as COVID-19 cases rise across North Carolina.

“The stress on us is the most profound I’ve ever experienced running camp,” Lemel says. “It’s petrifying to open another session, because we’re in Ground Zero.”

Keeping distance and logging on

Laura Blaisdell shares these feelings of determination and stress. A pediatrician by training, Blaisdell moved to Maine in 2005, where her husband is the third-generation owner of Camp Winnebago, a boys' camp in Fayette. Ever since, she’s worked each summer as the camp’s medical director.

In 2012, Blaisdell—who also has a master’s in public health—co-authored a study on how the 2009 H1N1 swine flu spread through Maine’s residential summer camps. But COVID-19 has challenged her in ways even she didn’t expect, from the elusive nature of its symptoms to the size of the national caseload.

Still, Blaisdell and others have worked around the clock to steer the camp industry through COVID-19’s choppy waters. Earlier this year, the American Camp Association and the YMCA released a 90-page “field guide” advising day and overnight camps on how to implement public health guidelines from the CDC.

Each individual cabin or class keeps its contact with the rest of the camp population to an absolute minimum. The grouping helps blunt camp-wide outbreaks by making it easier to keep any new cases isolated.

Rather than eliminate the risks of COVID-19—which can’t be done—the plan tries to lower and manage those risks. For example, the guidelines encourage parents to track their children’s symptoms, if not quarantine them outright, for the two weeks before camp. Staff are also urged to quarantine on-site for two weeks before the arrival of campers, whose temperatures and symptoms should be monitored daily.

All the standard rules apply—frequent handwashing, mask-wearing, and keeping at least six feet of distance—but medical directors such as Blaisdell have introduced a spin on social bubbles. Each individual cabin or class keeps its contact with the rest of the camp population to an absolute minimum. The grouping helps blunt camp-wide outbreaks by making it easier to keep any new cases isolated.

On August 26, Blaisdell and colleagues published a report on the efforts taken by Camp Winnebago and three other Maine overnight camps to prevent infection with COVID-19. Of the 1,022 attendees and staff across the four sites, only three people tested positive during the several weeks of camp. The camps also managed to prevent any secondary transmission, suggesting the many-layered approach blunted the disease’s spread.

Such bubbling is harder for day camps, given kids, staff, and parents are coming and going regularly. But versions of it are doable. At the Children’s Theater of Charlotte in North Carolina, day campers and staff have to log their symptoms into a smartphone app every day. Cohorts of campers also stay with the same instructor throughout the duration of camp, to minimize mixing. Steven Levine, the director of production at the Children’s Theater of Charlotte, adds that they set up live-streaming of the day’s events, just in case campers fall ill or become uncomfortable with physically attending camp.

Some youth organizations have had so much success with virtual camp, they plan on making it a permanent offering. The Girl Scouts of Southern Arizona, which serves more than 5,000 girls across the state, decided in the spring to go fully online. For “Camp Log On,” scouts received a “camp-in-a-box” in the mail, filled with crafting materials, patches, and camp T-shirts. The girls logged on to Zoom and spent a few hours each day with their fellow campers. To help families without internet access more easily attend Camp Log On, the Girl Scouts of Southern Arizona extended their buildings’ WiFi networks to the parking lots. For future editions of the virtual camp, the organization also is trying to build a “lending library” of laptops.

“We had been toying with virtual for a long time, but we hadn’t really been able to fully launch something,” says Kristen Garcia-Hernandez, CEO of Girl Scouts of Southern Arizona. “It’s clear to us now that we need to keep a third lane available and have that virtual camp experience.”

Progress and lessons for schools

While summer isn’t over yet, many camp organizers interviewed by National Geographic said they had no known cases of COVID-19, or had successfully isolated cases before the virus could spread. “I’m in the middle of the sixth inning; the game’s going well,” says Steve Baskin, owner and director of Camp Champions in Marble Falls, Texas. “I don’t want to blow it.”

Not all child-care facilities have made it through the summer unscathed. Brown University economist Emily Oster has been crowdsourcing a survey of daycares, summer schools, and camps—including Camp Champions and Keystone Camp—to infer the virus’s prevalence in these settings. Though Oster says the data aren’t ideal, they do suggest that many child-care centers have prevented clusters of cases from forming.

Aside from the unnamed camp in Georgia, other camps have had suspected outbreaks. Allaso Ranch, a retreat center in Hawkins, Texas, held church camp sessions in July that campers’ parents say caused between 30 and more than 80 cases of COVID-19, according to the Fort Worth Star-Telegram and two parents interviewed by National Geographic. Grapevine, Texas’s Fellowship Church—which owns Allaso Ranch—hasn't made any public statements on the cluster’s actual size, and the Texas Department of State Health Services doesn't release coronavirus data on individual facilities.

Allaso Ranch had a COVID-19 plan, including daily temperature checks, but it didn’t require campers to wear masks. Pictures posted on Instagram show that at one point this July, more than 140 mask-less teenage campers were packed together at the facility for a group picture. In other images, dozens of campers are seen attending an indoor worship concert, with no apparent face masks or physical distancing.

In a statement to the Star-Telegram, a spokesperson for Fellowship Church said the church followed CDC guidelines. The spokesperson also said Allaso Ranch contacted parents if campers developed symptoms or were in close contact with potential cases. (Allaso Ranch and Fellowship Church did not respond to National Geographic’s requests for comment.)

With the Georgia outbreak, the CDC notes that the staff didn’t require cloth face masks for campers, nor did it open windows and doors for increased ventilation. “The multiple measures adopted by the camp were not sufficient to prevent an outbreak in the context of substantial community transmission,” the report’s authors write.

Coronavirus is the great masquerader in children.

LAURA BLAISDELL, PEDIATRICIAN AND MEDICAL DIRECTOR, CAMP WINNEBAGO

Such an incident explains why medical staff at camps of all ages have been on edge. Blaisdell says that in the case of H1N1, influenza’s obvious symptoms made tracking it easy. At the Georgia camp, a quarter of the confirmed COVID-19 cases were asymptomatic. And even when symptoms do appear, the coronavirus doesn’t always manifest in kids the way it does in adults; the disease might be lurking in any stomach ache, bout of diarrhea, or case of the sniffles.

As a precaution, some camps have quarantined children for illnesses that turned out to be asthma or allergies. “Coronavirus is the great masquerader in children,” Blaisdell says. (Find out more about what we do—and don’t—know about COVID-19 and children.)

Another challenge: We still don’t understand how effectively children can spread COVID-19, though emerging research does suggest risks of transmission. For instance, one recent contact-tracing study from South Korea found that 10- to 19-year-olds spread the virus just as effectively as adults do. In another study published July 30 in JAMA Pediatrics, researchers found that children under 5 with COVID-19 had as much viral genetic material in their nasal passages as older children or adults, if not more.

By itself, this finding doesn’t necessarily mean that young children can shed large amounts of infectious virus. However, one small-scale study in Switzerland found that the amount of viral genetic material in nasal swabs correlated with the ability to isolate infectious viruses from children with symptoms of COVID-19.

“How contagious are children, [and] how likely are they to pass the virus on to other children, to teachers, or to their parents? We still don’t know the answer to that definitively,” says Dimitri Christakis, a Seattle Children’s Hospital pediatrician who co-authored a U.S. National Academies study on reopening K-12 schools amid COVID-19.

There’s also the problem of cost. Camp directors are well aware that adapting has taken resources: more staff, more cleaning supplies, more tests, more time, and more money. Not all camps, or child-care settings writ large, can bring the same resources or facilities to bear.

Safely running and attending camp during a pandemic is a privilege—one that highlights the economic and health inequities of the American summer, a gap that will only become starker as students return to school in the fall.

“Many of the inequities and disparities along racial and ethnic lines in the U.S. are perhaps even more visible now, given the context,” says Rachel Thornton, an associate professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University who co-authored a 2019 study of summertime for the National Academies.

Camps have also noticed the indirect toll that coronavirus is taking on kids. Months of isolation and social distancing have left some kids physically out of shape, Blaisdell says. Camp staff see a newfound anxiety of crowds in some campers, as well as the mental anguish the past few months have brought. “Normally, we might have one child that’s using Zoom to talk with a therapist—we’ll have a dozen this summer,” Baskin says.

Some experts are documenting these camp lessons so schools can learn from them and adopt best practices. The American Camp Association plans to do a retrospective survey of camps later this year, and Blaisdell has been collecting data on four Maine camps throughout the summer.

Christakis says that camps’s successes and failures could provide a “very useful” baseline for schools, but he and others lament the lack of a clear national strategy for monitoring COVID-19’s spread through child-care settings.

“There wasn’t the bandwidth, there wasn’t even the testing capacity, when we started … [that] should be prioritized, because we need to answer these questions,” Christakis says.

For Lemel, Keystone Camp’s director, the stakes are too high for the nation to get reopening schools wrong—a message she’s also trying to carry into local government. When Lemel isn’t at camp, she's a commissioner in Transylvania County, North Carolina, where Keystone is located, and she chairs the state’s Association of County Commissioners' Committee on Health and Human Services.

“Understand the energy and effort that was invested to make [camp] happen, but additionally, how incredibly important it is that we honor our children having childhoods,” she says. “Those are the lessons that we need to remember and we’ve got to make happen. We’ve just got to.”