How to Fix America’s Confusing Voting System

How to Fix America’s Confusing Voting System

By Aliyya Swaby and Annie Waldman, ProPublica, September 12, 2022

Photos usable. word count: 2208

Faye Combs used to enter the voting booth with trepidation. Unable to read until she was in her 40s, she would struggle to decipher the words on the ballot, intimidated by how quickly the people around her finished and departed. “When the election was over, I didn’t even realize what I had voted for because it was just so much reading,” she said.

Combs’ feelings of insecurity and disorientation when faced with a ballot are not unusual. Voters with low literacy skills are more likely to take what they read literally and act on each word, sometimes without considering context, literacy experts say. Distractions can more easily derail them, causing them to stop reading too soon.

“I’ve seen people try to read [the ballot] left to right and end up skipping entire contests,” said Kathryn Summers, a University of Baltimore professor who has spent decades studying how information can be made more accessible. She has found that voters who struggle to read are also more likely to make mistakes on their registration applications, such as writing their birth date incorrectly or forgetting to fill in the check box that indicates they are a citizen, either of which could lead to their vote being rejected.

As a ProPublica investigation found, today’s election system remains a modern-day literacy test — a convoluted obstacle course for people who struggle to read. Though many people may require assistance with registration or at the ballot box, some counties and states have made it more challenging to secure help.

Experts say that redesigning both the registration and election processes to be more accessible will allow more people to vote without assistance and participate more robustly in democracy. Ballots and forms should be simply written and logically laid out, jargon should be stripped from instructions and ballot amendments and, if possible, new forms should be tested on a diverse group of constituents.

Such reforms can be expensive and time-consuming, which stops some states and municipalities from taking on the task, said Dana Chisnell, who co-founded the nonprofit Center for Civic Design to help states and counties develop accessible voter materials. “They may have old voting systems that they’re holding together with duct tape and baling twine because they can’t afford to replace them or there were other priorities in the county,” she said.

But numerous examples show that when such changes are made, more votes get counted. “If we make it better for people with low literacy, it will actually be better for everyone,” Summers said.

Improving Ballot Design

As ProPublica has written, bad ballot design can sabotage up to hundreds of thousands of votes each election year. After the confusing butterfly ballot infamously wreaked havoc in the 2000 presidential election in Florida, the federal government increased its oversight and regulation of local election administration, including by issuing voluntary guidelines for how ballots and election materials should look. But states and counties continue to wind up with miscast or uncast votes as a result of design failures.

In 2018, for example, Florida’s Broward County used a ballot where the names of Senate candidates were listed at the bottom of a column, under a long list of instructions.

The Fight Against an Age-Old Effort to Block Americans From Voting

How We Analyzed Literacy and Voter Turnout

How to Vote: A Quick and Easy Guide

In most of the state, where other ballot designs were used, the Senate race drew about the same number of votes as the governor’s race. But in Broward County, a Democratic stronghold, fewer people voted for Senate than for governor, which was the race listed at the top of the second column. It’s likely that many people simply missed the Senate race at the bottom of the page. This discrepancy amounted to around 25,000 votes that were never cast. Republican Rick Scott won the race by about 10,000 votes.

Improving design has resulted in fewer skipped races and rejected ballots. The Center for Civic Design has created free online guides for designing accessible forms, which are intended to help local election officials short on resources.

If the essence of democracy is making sure that everyone who is eligible can vote, the election process should lean toward inclusion and accessibility, said Whitney Quesenbery, co-founder and executive director of the center. “Someone who has decided to vote ought to have a fair shot at getting their ballot counted,” she said. “The way you make sure that it gets honored is by telling people what they have to do in a clear way.”

Accessibility experts like Quesenbery say that these changes can improve the voting process for everyone, but especially for voters with limited reading abilities.

In 2010, New York voters got confusing messages if they accidentally overvoted — that is, voted for too many candidates — using machines made by two companies, Election Systems and Software and Dominion. The electronic screen on ES&S machines featured a red button saying “Don’t Cast — Return Ballot” and a green button saying “Accept.” Similarly, the Dominion machines featured a red button labeled “Return” and a green button labeled “Cast.” It was unclear which button would actually allow voters to fix the problem and many pressed the green button, which submitted their incorrectly filled-out ballot and meant that their vote was not counted at all.

As a result of a lawsuit that the Brennan Center for Justice and other groups filed against New York election officials, ES&S changed the messages on its buttons before the 2012 election, but Dominion did not get final permission for similar changes in time. The new buttons on ES&S machines gave voters the option to either “correct your ballot” or “cast your ballot with mistakes” — a much easier choice to understand than the previous options. That election year, rates of overvoting declined on both machines, but ES&S machines saw twice as big a drop as Dominion machines.

ES&S spokesperson Katina Granger said the accessibility changes for that election show “the need to continually obtain real world feedback from both customers and usability experts.” Dominion did not respond to ProPublica’s emailed questions.

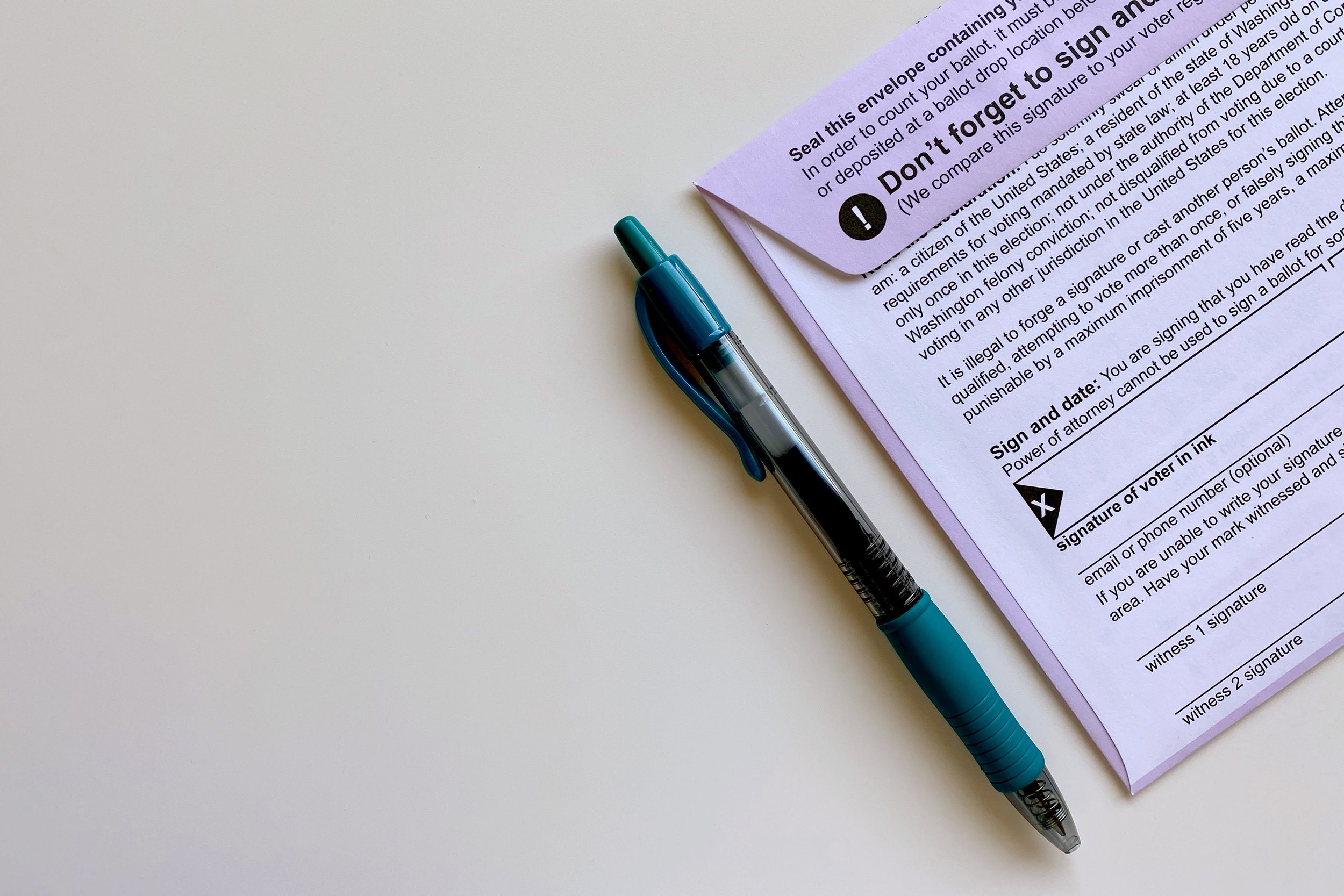

In advance of the 2014 election, Florida’s Escambia County redesigned its absentee ballot forms to format instructions as a checklist on the outside of the envelope, add simple illustrations and place a colored highlight over the spot where voters were supposed to sign. Many states, including Florida, require absentee ballots to be rejected if a signature is missing or doesn’t match other records. The new design’s emphasis on providing a signature reduced the share of ballots that were missing a signature by 42% between 2014 and 2016, and reduced by 53% the share of ballots that were rejected even after voters were offered a chance to add their signatures.

Similarly, New York redesigned its statewide absentee ballot template in 2020. The number of rejected absentee ballots in New York City decreased from around 22% in that year’s primary to just 4% by the general election.

Fixing Voter Registration

Many states have redesigned their voter registration forms, making the very first step in the election process more accessible for voters with low literacy skills. In 2015, when Pennsylvania launched online voter registration for the first time, state elections officials worked with the Center for Civic Design to test early versions with residents of the state. Their input helped officials design final versions of both online and paper forms with simplified language and minimal text on the page. The sections on the paper application are more clearly defined, with the instructions on the left and the voter tasks on the right. Pennsylvania noticed a decrease in rejected voter registration forms since the launch of the new forms, according to Department of State spokesperson Grace Griffaton, but could not separate the effect of the simpler design from the launch of online registration.

States like Colorado, Vermont and New York have created similar designs.

This year, Vermont debuted its new online registration form, completed with assistance from the Center for Civic Design, according to Secretary of State Jim Condos. Election workers had struggled to read voters’ handwriting on the previous form, which featured cramped spaces where residents had to fill in their information. The new form is much easier to fill out and read. “It’s really about making sure the language is simple enough but to the point,” Condos said.

Learning From Other Countries

The United States has some of the lowest voter registration and turnout rates among its international peers. It also stands out for its relatively burdensome voting process. Many experts believe these two things are related.

Other industrialized countries with comparable or even lower literacy rates to the United States tend to have higher levels of voter turnout. One simple reason for their increased participation is that they make it easier to vote. Most of them have some form of compulsory or automatic voter registration in place, according to research from the Pew Research Center and the ACE Electoral Knowledge Network. Countries allow citizens to vote on Election Day without having to actively sign up beforehand, or they automatically register citizens who interact with government organizations, like motor vehicle departments or social service agencies. Other countries, like Australia, have gone further and made voting mandatory, and citizens who do not cast ballots may be subject to penalties.

In nations with automatic registration programs in place, the percentage of people who are signed up to vote is substantially higher than in the United States, where only 67% of the voting-age population is registered. By comparison, in Canada, 93% of the voting-age population is registered to vote, and similarly, that number is 94% in Sweden and 99% in Slovakia, according to Pew. In the United Kingdom, where government officials seek out voters every year through nationwide canvassing, the registration rate is 92%.

Barry Burden, a professor and the director of the Elections Research Center at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, believes that in the United States, the registration step “is probably more of a deterrent to voter participation than we realize,” he said. “It’s a little challenging for most voters, but if a person doesn’t have the literacy skills or language skills to navigate that bureaucratic process, it could be a deterrent to even getting registered or getting a ballot in the first place.”

The United States is starting to shift its registration policies. Some states have initiated automatic voter registration programs, which use information from other government agencies to complete registration electronically unless people opt out. Since 2015, at least 15 states and Washington, D.C., have launched automatic registration programs, and the impact has been extraordinary — with new systems in place, registrations increased by 16% in Oregon, 27% in California and 94% in Georgia.

Allowing people to register on the same day they vote could increase participation, too. Voters who made errors earlier in the process would have another opportunity to register or fill out their ballots alongside election officials who could ensure their accuracy. As of 2012, states with same-day registration had, on average, 10% higher turnout than states without, according to the Center for American Progress.

Empowering Voters

Combs, who is now 78, no longer feels intimidated in the voting booth. She understands that there are many people like her, who have figured out ways to navigate the world without being able to read well enough to handle routine civic duties like voting.

At the age of 7, Combs was sexually abused by a stranger, a trauma that shadowed her childhood, she said, making it harder for her to remember the lessons she had learned in school. She pressured classmates for the answers to homework and exams, and her teachers passed her on from grade to grade. When she graduated from high school in Bakersfield, California, she said, she left with the secret that she couldn’t read. She was too ashamed to tell her husband until seven years into their marriage. She often brought him into the polling booth because she didn’t even know where to sign her name on the election forms.

Working as a manager of Berkeley’s Meals on Wheels program, Combs thought she was hiding her inability to read from her coworkers — until one day her secretary left a flyer on her desk about a local literacy program. She began learning with a tutor, strengthening both her ability to read and her desire to be more politically engaged. Since then, Combs has made it her mission to empower people to learn how to read and participate in democracy.

She now works with the Key to Community Project, which guides struggling readers through the voting process, helping them develop skills to research candidates and understand how elections work. The nonpartisan project, led by people who learned to read as adults, is an extension of California Library Literacy Services, the country’s first statewide library-based literacy program. Literacy advocates argue that states should contribute more to adult education in order to increase workforce skills and democratic participation. Combs counsels participants in the California program not to worry about taking as much time as they need to understand the ballot.

“I know what the shame is, but you have to move beyond that shame,” Combs said. “That attitude about ‘My vote doesn’t count’ needs to be banished.”