Gun Buybacks Are Popular. But Are They Effective?

Gun Buybacks Are Popular. But Are They Effective?

By Matt Vasilogambros, Stateline, August 30, 2022

Photos not usable. word count: 1213

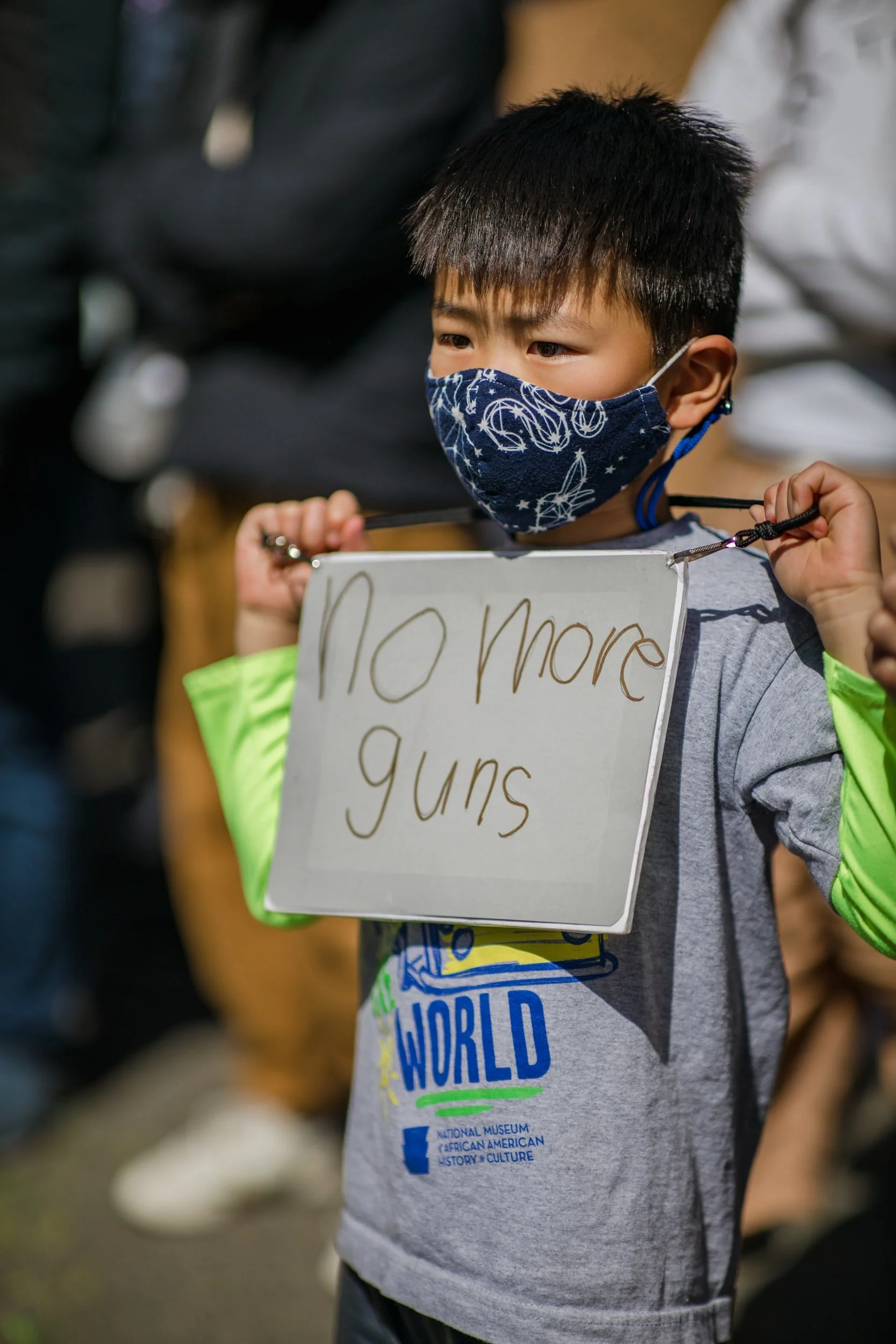

Two weeks ago, more than 160 gun owners in Richmond, Virginia, turned in 474 firearms in the city’s first-ever gun buyback event. City officials offered Walmart, Amazon and Kroger gift cards in various amounts for different unwanted firearms: $250 for assault-style weapons, $200 for handguns, $150 for rifles and $25 for non-functioning guns. No questions asked.

The event’s organizer, community activist Pati Navalta, knows all too well that guns that are stolen or bought on the streets are used in crimes; the men who shot and killed her son, Robby Poblete, in September 2014 during an attempted robbery in Vallejo, California, obtained their handgun illegally.

After her son’s death, Navalta launched the Robby Poblete Foundation to support gun buyback events throughout the country. The events have been held in several cities in California — including Vallejo — along with Augusta, Georgia, and Richmond, Virginia, and have collected more than 2,000 firearms. Reducing the number of guns in communities is essential, said Navalta.

“It’s really difficult to quantify the number of crimes prevented or the number of lives saved with every weapon we collect,” she said. “But the probability that a gun is used in a crime drops to zero when it gets bought back.”

Most police departments incinerate the weapons collected in such events, but the guns obtained in the Robby Poblete Foundation buybacks are used to create art exhibits through the foundation’s Art of Peace program to spark a discourse on gun violence—an homage to Poblete’s love of welding. Elsewhere, Oakland, California, forges them into garden tools, while Miami is sending guns from a buyback event this month to Ukraine for its defensive efforts against Russia.

American cities have been running buybacks since at least the 1970s, and they are broadly popular, even in conservative, gun-friendly states. Over the past two months, for example, gun buyback events in Houston netted 845 guns, Dane County, Wisconsin, received more than 500 guns and Spartanburg, South Carolina, collected 165 guns.

But while many communities include buybacks in their overall gun violence prevention strategies, most research shows these events are ineffective at reducing homicides and suicides.

“It’s a waste of resources if the entities that are sponsoring believe that it’s going to have a positive effect on reducing crime,” said Keith Taylor, an adjunct professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, which is part of the City University of New York system. “But if the purpose is to provide a means for individuals to get rid of weapons from their households that they don’t want to have anymore, it absolutely is a good option.”

Taylor, a former assistant commissioner at the New York Police Department, said if people wanted to get rid of unwanted guns, they don’t have to wait for a buyback event; most police departments will allow people to turn in firearms without a reward. But that doesn’t appeal to people who may use their firearms for crimes and a means of earning a living, he said.

Mark Anderson, a professor of economics at Montana State University, published a study with the National Bureau of Economic Research last year on the ineffectiveness of buyback events across the United States. The study cited research showing buybacks offer too little money, tend to take place in low-crime areas and collect firearms that tend to be older and less functional.

“Who’s choosing to turn their gun in?” Anderson asked. “It’s probably not the person on the margins whose gun we’re trying to get off the street. That gun from Grandpa is not the one that is going to be involved in a crime later on. It’s the voluntary nature of these things.”

An effective buyback would have to be a national event, paired with federal gun safety legislation, similar to what Australia did in 1996, said Bradley Bartos, an assistant professor of government and public policy at the University of Arizona, who studied the impact of the Australian model in a 2019 paper in Prevention Science.

After a man killed 35 people and wounded 28 others in a mass shooting in Port Arthur, Tasmania, Australia implemented federal gun safety legislation that in part banned automatic and semi-automatic rifles and shotguns. But it also included a mandatory buyback of newly illegal firearms. Officials collected and destroyed more than 650,000 firearms — about 20% of the guns in Australia. Gun-related homicides and suicides plummeted in the following years, research shows.

“Gun buybacks can work and have been shown to work in settings outside the U.S.,” said Bartos. “But those same factors in Australia aren’t present in the U.S.”

For one, Australia is geographically isolated, controlling the import of firearms at the federal level, he said. But more broadly, guns are too prevalent in the United States to substantially reduce their numbers voluntarily, he added. There are more guns than people in the U.S. For every 100 Americans, there are more than 120 firearms, according to a 2018 study by the Small Arms Survey, a Switzerland-based project that researches armed violence.

And even if a gun buyback event nets hundreds of guns, cities struggle with guns trafficked from states with less restrictive gun laws or from the influx of untraceable, 3D-printed “ghost guns,” he said.

Some community activists are trying to lobby their city officials to find ways to make buybacks more appealing, including through greater incentives.

The amount of money that officials offer for firearms at buyback events vary by community. While Nashville, Tennessee, offered $50 Kroger gift cards for all guns in its buyback event earlier this month, Columbus, Georgia, gave out $250 gift cards for any handgun, rifle or shotgun turned in at its event last month. Nashville netted 76 guns. Columbus, on the other hand, obtained 111 guns.

If the purpose of these events is to appeal to criminals who obtained their guns illegally, these financial incentives need to be much larger, said Jonathan Wilson, founder of the Fathership Foundation, a nonprofit that provides community education and workforce development in Philadelphia and in Wilmington, Delaware.

Ideally, local officials should offer at least $100 for rifles, $200 for small caliber revolvers, $400 for semi-automatics and $500 for assault weapons, he said.

While this would be substantially more money than communities currently offer, it would be far less than what they spend on prosecuting and jailing people who commit gun violence, said Wilson, who calls himself the “poster boy” of this issue, having been shot four times. He was paralyzed in a 2011 shooting and uses a wheelchair.

“They’re offering food vouchers for $100; it’s a joke,” he said. “We need to get more creative. I guarantee you if you offer $400 a gun, they’re going to be flying off the street.”

Although gun buybacks are by themselves inadequate to prevent gun violence, they do have a role to play in a broader approach to reducing the number of deaths and injuries from firearms, said Dr. Max Hazeltine, a general surgeon at the University of Massachusetts Memorial Medical Center.

Having treated “devastating” injuries from gunshots, he is convinced that a multipronged approach to gun violence prevention is required. And that includes gun buybacks, he said.

“A gun buyback in and of itself is helpful,” Hazeltine said. “But it’s not going to be as effective if it’s done in isolation.”