Emptier Jails Could Stay That Way

Emptier Jails Could Stay That Way By Daniel McGraw Reasons to be Cheerful May 4, 2020 (special rules: When sharing these stories on social media include a note about the story exchange with Reasons to be Cheerful tagged: Twitter: @RTB_Cheerful | Instagram/Facebook: @rtbcheerful)

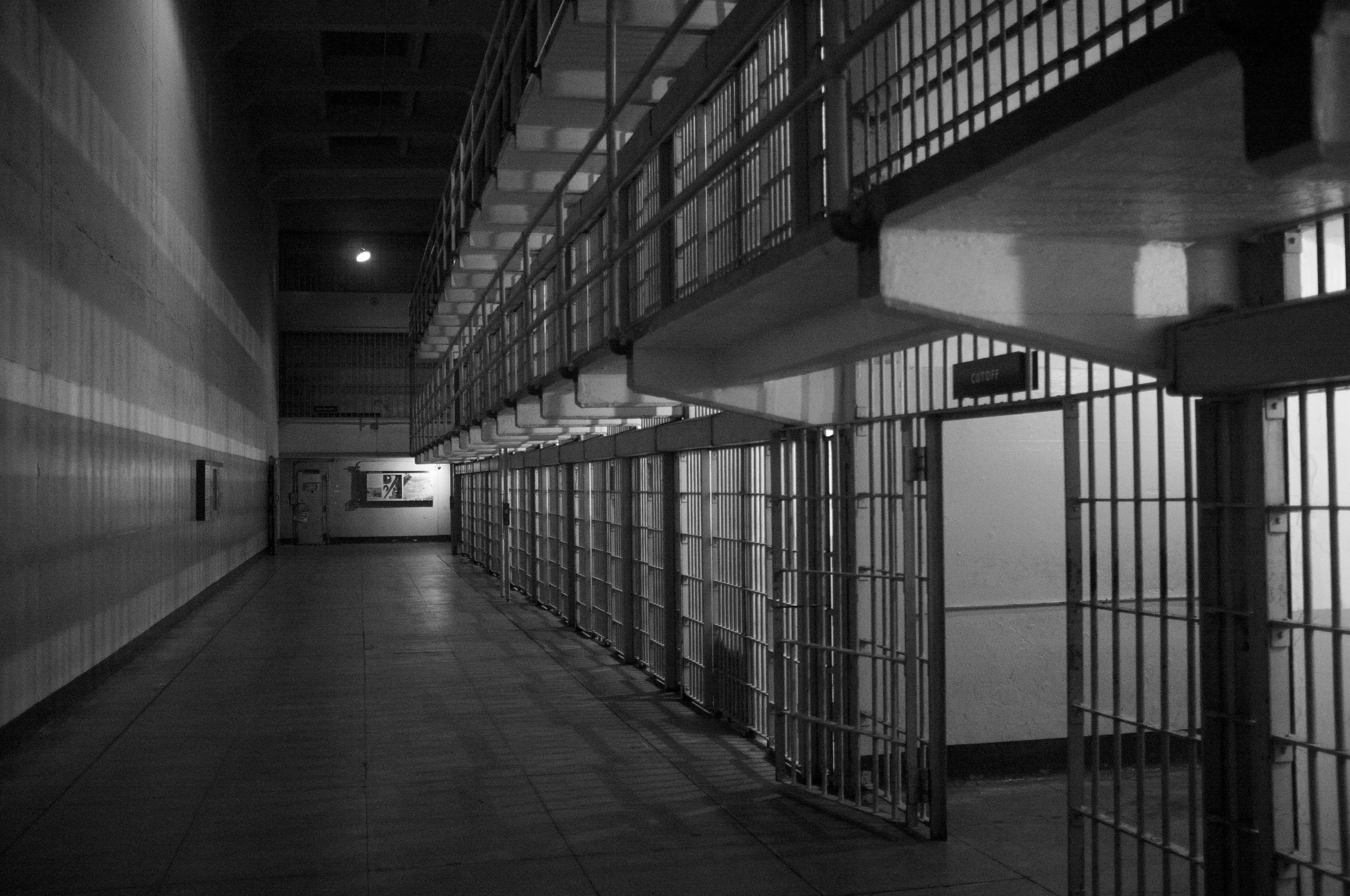

Covid-19 is showing us what ending mass incarceration could look like. Some judges and prosecutors like what they see.

A couple of months ago, the county jail in Cleveland started doing something that, prior to the pandemic, would have been unimaginable: It began releasing hundreds of inmates.

The problems at the jail were impossible to ignore. In 2018, the facility, which was designed to hold 1,765 inmates, was housing about 2,500. In a period of just six months that year, eight inmates died of various causes, prompting a U.S. Marshals investigation of the jail, which described its conditions as “inhumane.”

The jail’s troubles were emblematic of America’s mass incarceration problem, in which inmates spend months or years in jail on low-level charges or because they can’t afford bail.

But in Cleveland, this problem all but evaporated on March 10. That day, a group that included judges, prosecutors, law enforcement officials and public health advisors anxiously convened an emergency meeting. The state of Ohio had just recorded its first Covid-19 infection, and the group knew the virus could tear through the city’s over-capacity jail if something wasn’t done fast.

That’s when Dr. Julia Bruner, who oversees health care at the jail, stood up and told the attendees that the pandemic had just changed everything they knew about incarceration in Cleveland.

“She told the judges that, as coronavirus spreads, it could impact 30 percent of jail staff, spread through the jail quickly and leave officials with too few workers and too many inmates to treat,” reported the Cleveland Plain Dealer. According to Bruner, once she laid out that nightmare scenario, “There was very little resistance in the room.”

Soon after that, the county began releasing inmates who were awaiting trial or close to their release dates. For defendants who had just been convicted, judges handed down more lenient sentences. Cleveland’s overcrowded jail quickly began to depopulate — a total of about 900 inmates have been released so far, bringing the county’s inmate total down to about 1,000.

It was a drastic measure, taken in the heat of a crisis. As it happened, it was also a goal that many — on both ends of the political spectrum — had long hoped to achieve.

“The coronavirus pandemic gave our political leadership added ammunition and the critical mass to address something we’ve been trying to do for quite some time,” says Cleveland Municipal Court Judge Michael Nelson. “The virus helped push these proposed changes into real action. It is hard to predict what will happen when the virus becomes less of a safety issue, but I know this much: We won’t go back to how we were before.”

Justice reform gets a preview

What has happened in Cleveland is happening all over the country. Cities like New York, Los Angeles, Detroit, Houston, San Francisco, Austin, Chicago and New Orleans are releasing tens of thousands of inmates. In Denver, from March 1 to April 15, the average number of people in jail fell by 41 percent. Mobile, Alabama’s jail population went from 1,580 to 1,100 in four weeks. San Diego released 300 inmates in a single day in mid-April. In all cases, the released inmates were either at high-risk for coronavirus, low-level offenders, or near the end of their sentences.

Notably, the people advocating for these early releases are hardly social justice warriors. They are sheriffs, prosecutors and judges that have long been looking for an opening to reduce mandatory incarceration for low-level offenders – and lower the bail costs that keep many of the poor behind bars before trial. This is happening in both rural and urban areas, in red states and blue states, in places where prison reform has been on the table for years and in places where it has rarely been discussed.

“In the last decade or so there has been more of an opening for reconsideration on how many people we send to jail, and the current health crisis has opened that further,” says Marc Mauer, executive director of The Sentencing Project and one of the country’s leading experts on sentencing policy, race and the criminal justice system. “The discussion now is getting less political and more solution-oriented. That’s the difference now.”

The U.S. prison population began to rise in the mid-1970s, reaching double-digit annual percentage increases in the 1980s as almost every state adopted some form of mandatory sentencing and ramped up arrests for drug offenses. The 1994 federal crime bill contributed to the increase by expanding the death penalty, mandatory minimum sentencing, and incentives that encouraged states to adopt harsher punishments and limit parole.

The result? Between 1980 and 2020, while the U.S. population increased by about 45 percent, the prison population increased by 275 percent. Local jails also saw a big increase, with 223,000 people incarcerated in 1983 and about 630,000 today, about two-thirds of whom are unconvicted — they are simply awaiting trial or sentencing.

In recent years, reducing this incarceration rate has united advocates on the right and the left, who are by turns motivated by the human costs and the monetary ones. The Bureau of Justice Statistics estimates that the U.S. spends more than $80 billion each year to keep roughly 2.3 million people behind bars, or about $35,000 per inmate.

But is the answer simply to release inmates who are deemed low-risk, as is happening now? Does a solution that makes sense during a pandemic also make sense as permanent policy?

The last few years have provided some hints to that answer, as several states have moved to reform their bail systems, effectively doing in small doses what is now being done in a deluge.

New York is the most recent example, which earlier this year eliminated cash bail for misdemeanors and non-violent felonies. The reforms have succeeded in reducing the jail population, but have also drawn the ire of the NYPD, which has reported a rise in crimes like robbery since the reforms were enacted. “There’s a correlation” between bail reform and the increase in crime, the department’s commissioner said in January.

But advocates say it’s ridiculous to attribute a few months of data fluctuations to a single policy, and accuse reform’s opponents of cherry-picking their crime statistics. For instance, they point out, while robberies have gone up since the reforms, rapes and homicides have fallen. In his January report, the police department’s own statistician declined to attribute January’s rise in crime to bail reform. And research has suggested that the NYPD, which controls the city’s CompStat crime-data cruncher, may manipulate this data to sway public opinion on these issues.

Across the Hudson River, New Jersey provides a longer-term case study. Bail reforms implemented there in 2017 reduced the state’s jail population by 45 percent. Yet New Jersey has experienced no major upswing in crime. In 2016, there were 21,914 violent crimes in the Garden State. In 2018, post-reforms, there were 18,357.

In California, too, a series of reforms, lawsuits and ballot initiatives have reduced the incarceration rate significantly since its peak in 2006. As in New York, critics point to spikes in crime in California since the reforms began. For instance, in 2014, after voters passed Proposition 47, reclassifying many non-violent offenses as misdemeanors, a 12 percent increase in robberies and aggravated assaults followed.

But advocates for the reforms will tell you to look at the longer trend line: Those small spikes are overwhelmed by the broader decrease in crime — now the lowest it has been since the 1960s. “To look at it from a year-to-year basis is very short-sighted,” Michael Romano, the director of the Three Strikes Project at Stanford Law, told the Marshall Project. “We really have had a sustained downward trend over the past decade or two.”

Even if these spikes do correlate with policies that let some inmates out of jail, supporters say there’s a larger question society needs to ask itself: Can it tolerate a small and temporary uptick in minor non-violent crimes for the greater purpose of alleviating the devastation caused by mass incarceration? “If you wanted to have the safest community, you just would lock up everybody,” Judge Glenn Grant, administrative director of the New Jersey courts, told the New York Daily News. “But we are looking to try to balance presumptions of innocence versus public safety.”

Despite such appeals to fairness and decency, it may be the economic argument that becomes the more compelling one, especially as state and city budgets collapse, and the costs of housing thousands of low-level and unconvicted inmates mount.

“One would like to think the open-minded can see a significant reduction in the number of people in jail will have little effect on crime,” says The Sentencing Project’s Marc Mauer. “But all this will depend quite a bit on the larger issues of economic and social dynamics. The economic hit from [Covid-19] will be substantial to the country, and we will have to come together as a nation to bring the economy back to life. We will have to make cuts on government spending programs, no doubt.”