200 Schools, Universal Weekly COVID Screening: How ‘Assurance Testing’ Has Kept Thousands of Texas Students in Classrooms

By Bekah McNeel, The 74 MillionFebruary 28, 2021

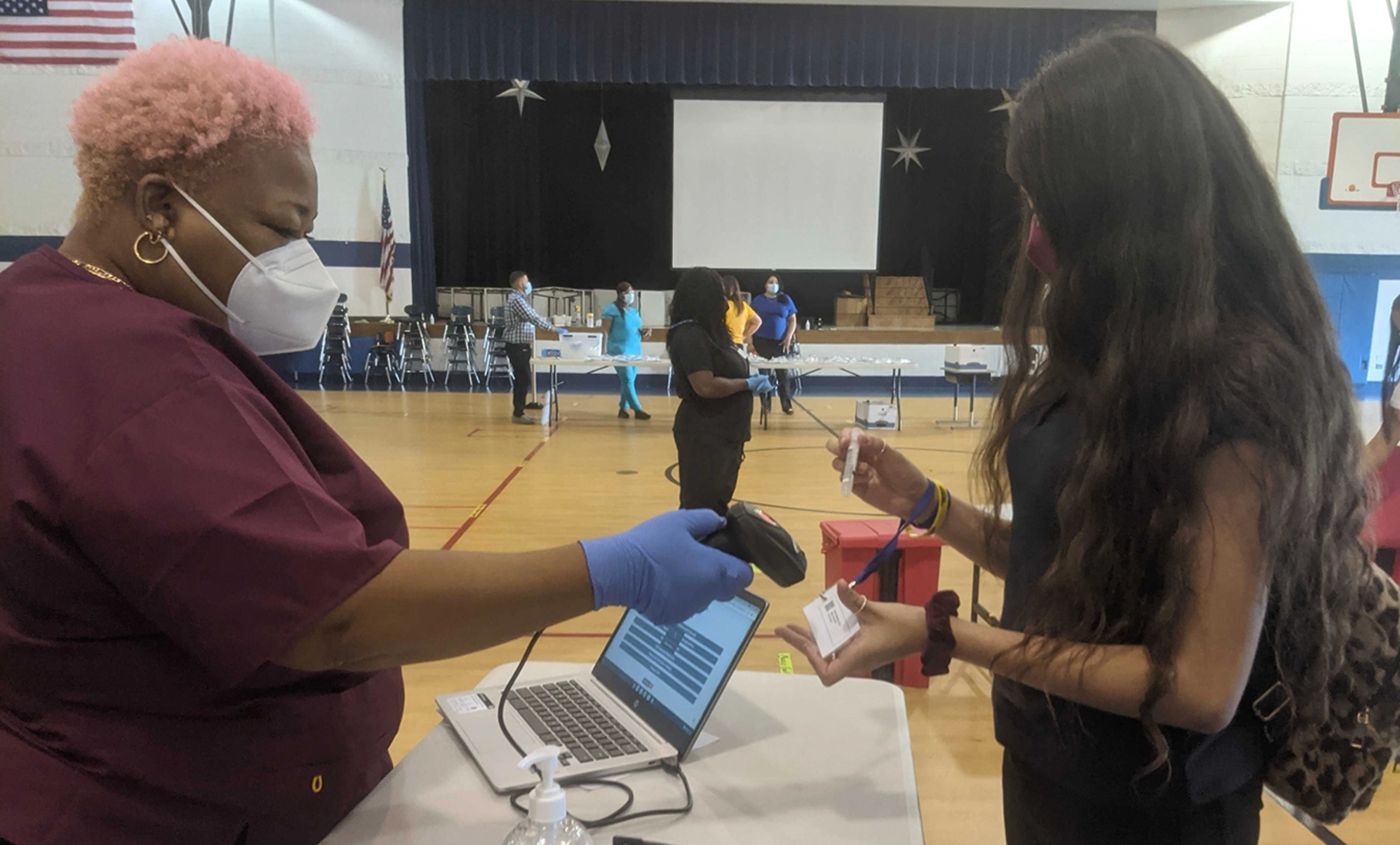

Photos available Lead image: Courtesy of Bekah McNeel

This piece is a part of “COVID Warriors: How Educators Are Saving the Pandemic Generation,” a two-week series produced in collaboration with the Solutions Journalism Network that explores what educators, schools, and districts are doing to prevent an entire generation of students from lost learning and its lifetime of consequences. Read all the pieces in this series as they are published here. Catch up on all of our solutions-based coverage here.

Every Friday since December, my kids head to school and do the same thing as thousands of other kids in San Antonio: They administer their own COVID-19 tests.

Under the watchful eye of teachers and technicians, wearing their masks and staying 6 feet apart, they walk with their classmates to the school auditorium, where they’re handed a nasal swab.

“It’s 1-2-3-4-5 little circles around the front of your nostril,” my 6-year-old daughter told me. “Not like those awful ones at the doctor.”

Both kids have had the deep-nostril COVID-19 tests before. They ended in tears and cupcakes.

Within the next 24 hours, I get the emailed link to both children’s test results.

“SARS-CoV-2 Not Detected.”

It feels good to know about my kids — and to know the testing is happening every week on 200 campuses around San Antonio, an unusual step that has made many parents and teachers feel better about in-person learning.

Determined to keep San Antonio schools open, the newly created nonprofit Community Labs is running an assurance testing operation at a size and scale unique in the country, officials said.

With $3.5 million in philanthropic startup money and operating costs covered by public CARES Act funding, the tests remain free to school districts, staff and the families they serve.

While many schools across the country randomly spot-test, or test students in higher-risk activities like sports, to test every single willing student and staff member weekly has been too costly for most school systems.

“It’s a game changer,” said San Antonio ISD Superintendent Pedro Martinez, adding the tests are an additional safety measure. Assurance testing isn’t a cure, he reiterated, but it has lived up to its name, giving teachers and parents the assurance needed to keep kids in school and continue doing what works — social distancing, hand washing and mask wearing.

In addition to feeling safer, experts say, the kids and the teachers actually are safer.

Widespread assurance testing has become a regular feature of guidance and recommendations for reopening schools around the country, with the Biden administration pledging $650 million to expand the practice.

When used regularly across an entire population, tests catch individuals who may have been spreading the virus without knowing it — a key concern in schools, as young people are more likely to have mild or no symptoms than adults. The more of those carriers who are sent home, the less the virus spreads.

“You’re combing the virus out of the population,” Community Labs President Sal Webber said.

An October pilot program ran in tiny Somerset ISD, southwest of the city. After four months of testing, Somerset’s on-campus positivity rate dropped from 1.4 percent to 0.7 percent.

San Antonio ISD, the largest district to use Community Labs so far, began testing in November. Even as the community positivity rate soared over 10 percent, the districts’ rate stayed at 1 percent, and Martinez had the data to prove it. When tests came back positive, contact tracing almost always led back to family gatherings or close contacts in the home, Martinez said. “We saw the Thanksgiving, the Christmas and the New Year’s cases, but we were able to catch them and send them home.”

However, the high level of COVID-19 in the community has made Martinez hesitant to bring more students back in person, even with the tests. He knows the multi-generational households and frontline workers in his community, and wants to be cautious while the numbers are high. Social distancing is key to San Antonio ISD’s plan, Martinez said, and that’s impossible to do with a full classroom.

“We’ve always been much more conservative and cautious simply because our population is higher-risk,” he said.

The district has also been engaged in a tug-of-war with its teachers union over the requirement to teach on campus. One teacher, who asked to remain anonymous given the tension, said she had been extremely anxious going back to school last semester, because she felt that many of the mitigation measures wouldn’t be fully effective when kids inevitably wore masks incorrectly, or weren’t thorough enough about hand washing. The testing is more regimented.

“The weekly testing does make me feel a little safer,” the teacher said, “Because of it, we have caught students who are asymptomatic spreaders, which we wouldn’t have been able to do without the testing. This hasn’t completely shut down the spread, but it has slowed it. Is it perfect? No. But it’s better than not testing at all.”

Even though one of the goals of the tests is to keep kids learning in person, Webber said, schools still need to make these cautious decisions. Testing works with other mitigation strategies, not in place of them.

“If anything, the testing is proving that all of the precautions that the schools are taking are completely working,” Webber said.

The Community Labs team considered all the resources available to create a testing system ideally suited for schools. They looked into several collection methods before settling on a swab in the front of the nostril, figuring that saliva collection would be too risky and cumbersome at schools and that the infamous deep-nostril swabs would result in lots of crying children. Anyone can opt out of the test, so they wanted to make it as painless as possible to maximize participation.

They went with a PCR test, as opposed to the less sensitive rapid-antigen tests being used by event venues, airlines and some businesses. Rapid tests give results on the spot, but Webber explained that Community Labs’ goal was to catch asymptomatic and pre-symptomatic cases, and PCR’s sensitivity is better for that. However, the turnaround time for PCR tests at most labs in the area is up to three days. By that time, he said, the kid has likely infected others.

“The biggest key we learned is that speed matters,” Webber said. To truly prevent spread, they needed to deliver test results in 24 hours or less.

Local biotech nonprofit BioBridge Global helped the start-up select equipment that was readily available to avoid supply chain delays. They then contracted with a company that provides vaccinations at schools, Coldchain Technology, because their teams were already familiar with the protocols for efficiently administering medical procedures. They continually worked to improve the Community Labs process until they could get both the speed and sensitivity they needed.

“We have caught many people up to 72 hours before they have symptoms,” Webber said. Those people can avoid spreading the virus, and can also get help for themselves sooner.

The nonprofit is able to get new schools up and running each week. Right now, they can add 10 to 20 schools per week, processing up to 16,000 tests per day.

The nonprofit has also created a toolkit to share with other cities and communities looking to replicate their model, a 70-page document Webber called a “Lab in a Box.” Some 30 cities are interested, but none have gotten a similar program up and running yet. “A lot of folks have gotten stuck on funding,” Webber said.

The initial $3.5 million to get the labs going came from local foundations and philanthropists — the 80/20 Foundation, the Kronkosky Charitable Foundation, The Tobin Endowment and the Alvarez family.

Most other PCR tests cost the client over $100, making widespread testing cost-prohibitive even after the initial outlay of funds. As a nonprofit, however, Community Labs offers the tests at about a third of the market rate. Each costs about $35, and the cost of transportation is included in that fee for schools, Webber said.

Using CARES Act funds, the county government covers this cost for some school districts, and the city has begun to pay for the lab’s services to be offered at three community centers. Community Labs is working with the remaining school districts not covered by the county to begin their testing program using state funds.

Even the historic freeze that gripped Texas in the week after Valentine’s Day did not stop San Antonio ISD from its regular COVID-19 testing. As city and county officials worried that warming centers, hotels and even refuge sought at the homes of friends and family could turn the storm into a superspreader event, the district announced it would test students on Saturday, before their return to school on Monday.

It was voluntary, of course, but we decided to go, as much for the peace of mind of my children’s teachers as for my own. I wondered how many of their classmates would show up after a dismal week of busted pipes, unreliable electricity and icy roads.

When we showed up 10 minutes before the testing began, the line stretched around the block. It went quickly, as kids moved efficiently through the familiar procedure. Exactly 12 hours later, the results hit my inbox.

“SARS-CoV-2 Not Detected.”